Essential Guide to the Quantity Theory of Money 2025

Why does inflation often surge when the money supply increases? The answer lies in the quantity theory of money, a foundational concept that has shaped economic understanding for centuries.

This essential guide explores the quantity theory of money as it stands in 2025, unpacking its origins, core mechanics, modern debates, and impact on global economies.

Curious about how money influences inflation, prices, and stability? The quantity theory of money offers a powerful lens for students, investors, and anyone eager to make sense of today’s complex financial world.

Join us as we break down its history, mathematics, controversies, and real-world significance. Ready to dive in and discover the forces shaping our economic future?

The Foundations of the Quantity Theory of Money

Understanding the foundations of the quantity theory of money is essential for grasping how changes in the money supply influence inflation and economic stability. This section explores the origins, core equation, and practical implications of this enduring economic theory.

Defining the Quantity Theory of Money

The quantity theory of money posits a direct, proportional relationship between the amount of money circulating in an economy and the general level of prices. This idea suggests that when the money supply increases, and all else remains equal, prices will rise accordingly.

The roots of the quantity theory of money trace back to the 16th century. Early thinkers such as Copernicus, Martín de Azpilcueta, and Jean Bodin observed that an abundance of money led to higher prices. Their insights emerged as Europe experienced the Price Revolution, a period when prices quadrupled over roughly a century. These historical episodes provided powerful evidence for the theory’s core principle.

Over time, the quantity theory of money became a cornerstone of both classical and monetarist economics. The theory assumes that changes in the money supply are the primary driver of inflation. For example, if the money supply doubles, and the velocity of money and real output remain constant, the overall price level will also double. This proportional effect is central to understanding inflationary surges throughout history.

Key contributors to the development of the quantity theory of money include:

- Copernicus (1517): Identified the link between money abundance and depreciation.

- Martín de Azpilcueta and Jean Bodin: Applied the theory to explain the Price Revolution in Europe.

- Later economists: Built on these foundations to formalize the theory’s mechanics.

For a deeper historical perspective on the Quantity Theory, see this comprehensive analysis of its origins and adaptability.

The quantity theory of money remains relevant for explaining both historical and contemporary inflationary episodes.

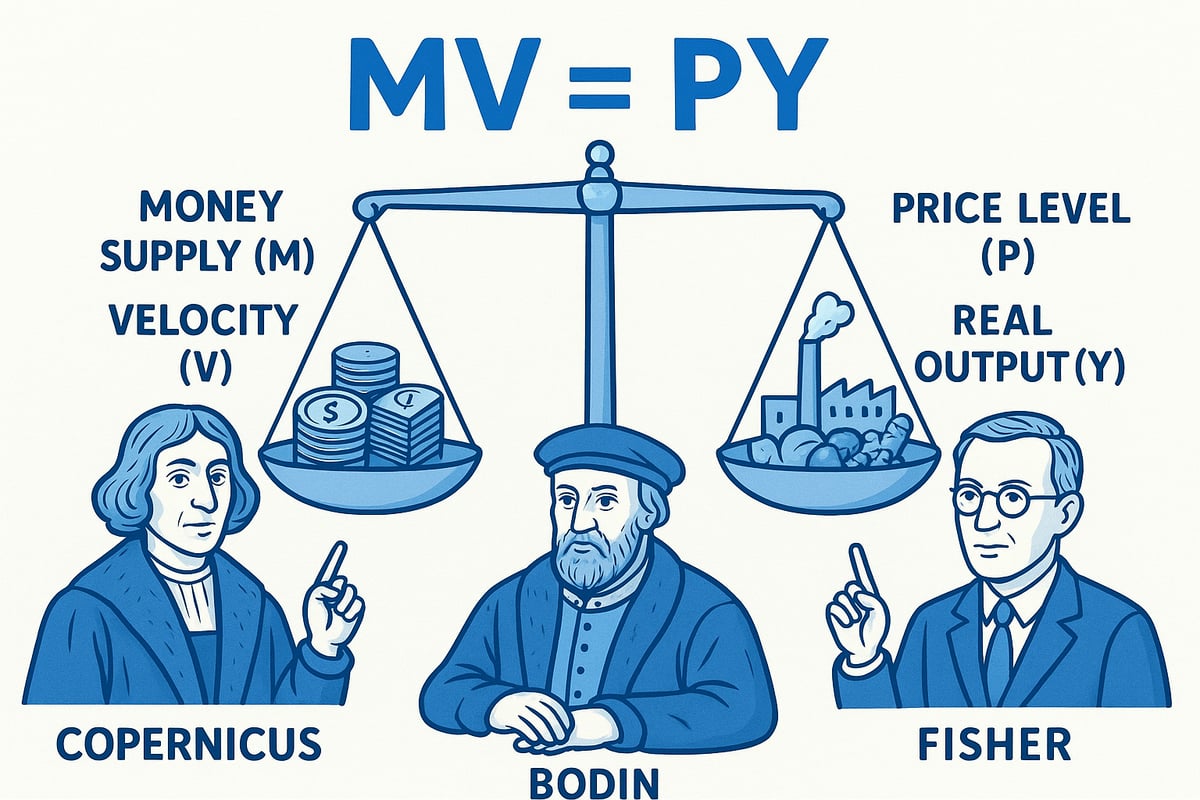

The Equation of Exchange: MV = PY

At the heart of the quantity theory of money lies the equation of exchange:

MV = PY

This formula links four fundamental economic variables:

| Symbol | Meaning | Description |

|---|---|---|

| M | Money Supply | Total amount of money in circulation |

| V | Velocity | Average frequency money is spent in a year |

| P | Price Level | General price of goods and services |

| Y | Real Output | Quantity of goods and services produced |

This equation is an accounting identity, capturing the flow of money and goods in an economy. Irving Fisher, a key figure in monetary economics, played a major role in formalizing this relationship. The Cambridge approach, developed later, emphasized the demand for money and introduced the “k” constant to express money held for transactions.

Let’s consider a simple example. Suppose an economy has a money supply (M) of $1,000, a velocity (V) of 4, and real output (Y) of 500 units. Using the equation:

$1,000 × 4 = P × 500

$4,000 = P × 500

P = $8

Here, the price level (P) is $8 per unit. If the money supply rises to $2,000 with velocity and output unchanged, the price level doubles to $16. This illustrates the proportionality at the core of the quantity theory of money.

The velocity of money is a crucial factor. While early versions of the theory assumed velocity was stable, historical data shows that it can fluctuate significantly, impacting the predictive power of the quantity theory of money. For instance, during certain periods, shifts in payment technology or financial innovation have caused velocity to change in unexpected ways, altering the link between money supply and price levels.

Understanding the equation of exchange helps clarify why the quantity theory of money remains a vital tool for analyzing inflation and monetary policy.

Historical Development and Key Contributors

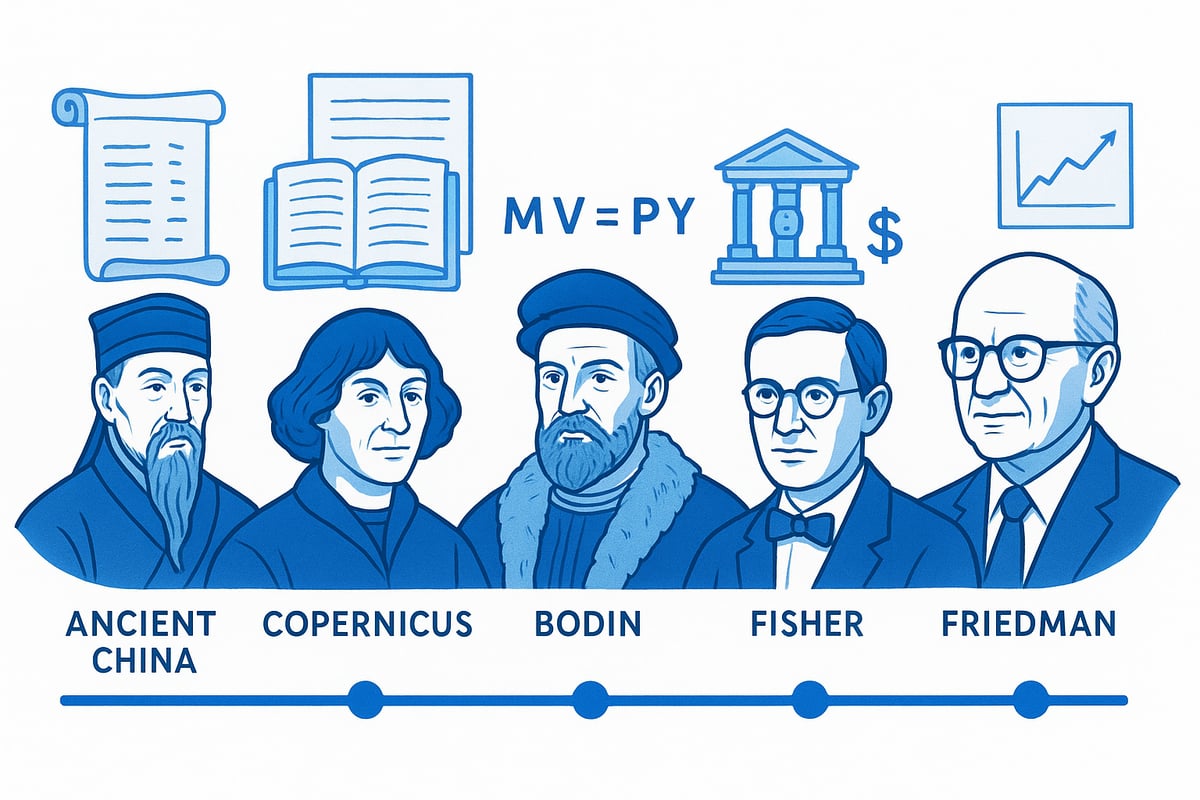

The evolution of the quantity theory of money is a story that spans continents, centuries, and schools of thought. Understanding its development provides essential context for how it shapes economic policy and debate today.

Early Origins and Evolution

The quantity theory of money traces its roots to ancient texts and early economic thinkers. As far back as the Guanzi in ancient China, scholars observed that the supply of money could influence prices.

During the European Renaissance, the theory took shape through the work of Nicolaus Copernicus in 1517. He proposed that an abundance of money led to the depreciation of its value, a principle central to the quantity theory of money. Martín de Azpilcueta and Jean Bodin expanded this idea to explain the dramatic price increases during the 16th-century Price Revolution, when European prices quadrupled as silver from the New World flooded the economy.

John Locke later explored the velocity of money, emphasizing how quickly money circulates through the economy. David Hume, in 1752, built on these ideas, introducing the concept of the neutrality of money in the long run. Collectively, these thinkers established the foundation for the quantity theory of money, which remains a cornerstone for understanding inflation and monetary dynamics.

20th Century Advances

In the 20th century, the quantity theory of money was refined and empirically tested. Irving Fisher played a pivotal role by formalizing the equation of exchange, MV = PY, providing a mathematical framework for the theory. Alfred Marshall and the Cambridge school shifted the focus toward the demand for money, introducing the cash-balance approach and the "k" constant.

Milton Friedman’s 1956 restatement revitalized the quantity theory of money, making it central to monetarist economics. Along with Anna Schwartz, Friedman conducted extensive empirical research, culminating in "A Monetary History of the United States." Their work influenced central banks, prompting institutions like the Federal Reserve, Bank of England, and Bundesbank to adopt money supply targeting in the 1970s and 1980s. Results were mixed, as the direct link between money growth and inflation sometimes faltered.

For a deeper look at how the relationship between money supply and inflation has changed over time, see this empirical analysis of QTM from 1870 to 2020. This research highlights both the enduring influence and the challenges faced by the quantity theory of money in practice.

Shifts in Economic Thought

By the late 20th century, the strict application of the quantity theory of money began to wane. Central banks found that targeting the money supply did not always yield predictable control over inflation, largely due to shifts in money velocity and financial innovation.

The focus turned toward inflation targeting and the use of interest rates as primary policy tools. Despite these changes, the quantity theory of money continues to inform debates about monetary policy, especially during periods of rapid inflation or unconventional policy experiments.

Today, the theory remains a vital reference point, offering both historical insight and a framework for ongoing discussions about the relationship between money, prices, and economic stability.

Mechanics and Assumptions of the Quantity Theory

Understanding the mechanics and assumptions of the quantity theory of money is essential for interpreting monetary policy and inflation. This section explores the foundational beliefs, implications, criticisms, and modern adaptations of the theory.

Core Assumptions Explained

The quantity theory of money relies on several key assumptions that form the backbone of its logic. First, it assumes that the velocity of money, which measures how often money changes hands, is constant or at least predictable in the short to medium term. Second, the theory considers real output (Y) as exogenously determined, meaning it is set by factors like technology and resources rather than by the money supply itself. Third, it presumes the central bank fully controls the money supply, treating it as an exogenous variable.

These assumptions support the idea that changes in the money supply directly influence the price level (P), provided velocity (V) and output (Y) do not shift. The equation behind the quantity theory of money, MV = PY, summarizes this relationship. For instance, if the money supply doubles while velocity and output remain stable, the price level should also double. This simplicity is both the strength and limitation of the quantity theory of money.

A summary table of these assumptions:

| Assumption | Description |

|---|---|

| Velocity (V) | Constant or predictable |

| Real Output (Y) | Exogenous, not affected by money supply in long run |

| Money Supply (M) | Under central bank control, exogenous |

| Price Level (P) | Determined by M and V, given Y |

Theoretical Implications

Based on its assumptions, the quantity theory of money leads to clear and direct implications for inflation and economic policy. If the money supply increases and both velocity and real output stay unchanged, the price level must rise. This outcome is foundational: inflation occurs when money supply growth outpaces real output growth.

The theory also implies the neutrality of money in the long run. In other words, altering the money supply affects only the price level, not real economic output. Policymakers using the quantity theory of money expect that, while short-term effects might exist, sustained changes in M will translate into proportional changes in P over time.

To illustrate, consider this simple calculation using the MV=PY equation:

If M = $1 trillion, V = 4, Y = $2 trillion:

P = (M x V) / Y = ($1T x 4) / $2T = 2

If M doubles to $2 trillion (V and Y constant):

P = ($2T x 4) / $2T = 4

Price level doubles.

This example demonstrates how the mechanics of the quantity theory of money predict inflation with changes in M.

Critiques of Assumptions

While the quantity theory of money offers a straightforward framework, several critiques challenge its core assumptions. First, velocity is not always stable. Technological advances, changes in payment systems, and shifts in consumer or business behavior can cause velocity to fluctuate unpredictably.

Second, the assumption that central banks control the money supply completely is often unrealistic. In many economies, commercial banks create money through lending, making the money supply partly endogenous. Third, real output may not be entirely independent of monetary factors, especially in the short run.

Key critiques include:

- Velocity can change due to innovation or financial crises.

- Money supply may respond to economic conditions, not just central bank actions.

- Short-run non-neutrality: monetary policy can impact output and employment.

- The Keynesian critique argues that increased money supply can reduce velocity, offsetting inflationary pressures.

These points reveal why the quantity theory of money may not always predict real-world outcomes with precision.

Real-World Examples and Data

Historical experience shows both the strengths and limits of the quantity theory of money. During the 1970s and 1980s, many advanced economies saw rapid money supply growth alongside high inflation, aligning with the theory's predictions. However, empirical evidence has also shown periods when increases in M did not result in proportional rises in P.

One notable example is the aftermath of the 2008 financial crisis. Central banks in the US and Europe expanded the money supply dramatically, yet inflation remained subdued for years. This divergence raised questions about the reliability of the quantity theory of money as a standalone guide for policy.

Recent studies, such as the Policy lessons from recent US inflation, examine how new dynamics, including shifts in velocity and global factors, have influenced inflation outcomes. These findings highlight the need to consider both money supply and velocity for a complete view.

Modern Refinements

Contemporary economics has refined the quantity theory of money to address its limitations and adapt to modern realities. Monetarists, led by Milton Friedman, advocate for steady, predictable growth in the money supply to ensure price stability. In contrast, Keynesian and post-Keynesian economists emphasize the roles of fiscal policy, interest rates, and expectations, arguing that money demand and velocity are less predictable.

Most major central banks have shifted away from strict money supply targets, focusing instead on inflation targeting and managing interest rates. This shift reflects the recognition that the traditional quantity theory of money cannot alone explain complex, modern economies.

Today, the quantity theory of money remains a valuable tool for historical perspective and for understanding the links between money, prices, and output. However, it is used alongside more flexible frameworks that incorporate changing economic conditions and behaviors.

Debates, Criticisms, and Alternative Theories

Why do economists still debate the quantity theory of money after centuries of analysis? To answer this, we need to explore its critics, real-world performance, and the alternative frameworks that challenge or refine its claims.

Monetarism vs. Keynesianism

The quantity theory of money has stood at the heart of one of economics’ great divides: monetarism versus Keynesianism. Monetarists, led by Milton Friedman, argue that controlling the money supply is the key to managing inflation. They see the quantity theory of money as both a predictive tool and a policy guide. In this view, if the money supply grows faster than economic output, inflation is inevitable.

Keynesians, however, offer a different perspective. They argue that changes in the money supply do not always translate into changes in prices. According to Keynesians, the velocity of money can fall during economic slumps, neutralizing the inflationary impact of monetary expansion. They introduced concepts like the liquidity trap, where increases in the money supply are simply hoarded rather than spent, limiting the quantity theory of money’s predictive power.

This fundamental disagreement shapes how policymakers respond to recessions and inflation. Should central banks focus on money supply, or are interest rates and fiscal policy more effective? The debate continues to influence economic thinking worldwide.

Empirical Evidence and Real-World Challenges

Empirical tests of the quantity theory of money have produced mixed results. During the 1970s and 1980s, many central banks adopted money supply targets, expecting to tame inflation. While some countries saw success, others found that inflation did not always track money supply growth. For example, Japan’s “lost decades” featured large increases in money supply but persistent deflation, challenging the theory’s universality.

One major complication is the velocity of money. In practice, velocity is not stable. It can fall during crises or periods of uncertainty, making the relationship between money supply and prices less predictable. The global financial crisis and the COVID-19 pandemic offer recent examples. Despite huge expansions in money supply, inflation remained subdued for years—until a recent resurgence. For a deeper analysis of these dynamics, see Is the Quantity Theory Dead? Lessons from the Pandemic.

The real world is complex, and the quantity theory of money must contend with changing behaviors, technological shifts, and evolving financial systems. These factors often blur the direct link between money and inflation.

Alternative Theories and Modifications

Recognizing the limits of the quantity theory of money, economists have developed alternative approaches. The Cambridge cash-balance approach, for instance, shifts focus to the demand for money, introducing a new constant to capture how much wealth people choose to hold in cash. This model highlights that money’s impact depends on both supply and demand factors.

Endogenous money theory takes things further. It argues that banks, not central banks, are the main creators of money through lending. This view challenges the assumption that central banks can fully control the money supply. Modern Monetary Theory, or MMT, offers another departure. It claims that government spending is the main driver of inflation, not the quantity theory of money’s simple link between money and prices.

These alternatives illustrate the ongoing search for models that better reflect the complexities of modern economies.

Key Arguments and Insights

The quantity theory of money remains influential because of its simplicity and historical power to explain inflationary episodes. Yet, its reliance on strong assumptions—such as constant velocity and exogenous money supply—limits its practical application. Critics argue that it oversimplifies the real world, where money creation, velocity, and price dynamics are constantly in flux.

Recent decades have seen the velocity of money decline, even as money supply has soared. Digital currencies and unconventional monetary policies further complicate the picture. The debate now centers on whether the quantity theory of money can adapt to these changes or if new frameworks are needed for the digital age.

Despite its critics, the theory continues to serve as a reference point in economic debate, helping analysts interpret both historical and current monetary phenomena.

The Quantity Theory of Money in Practice: Policy and Economic Impact

Understanding the quantity theory of money in practice means exploring how it shapes real-world monetary policy and impacts economies around the globe. This section examines how central banks use the theory, its predictions for inflation and deflation, and the effects of financial innovation. We also consider the modern relevance of the quantity theory of money in 2025, differences across regions, and practical lessons for decision-makers. By breaking down these issues, we see how the theory’s principles play out in policy debates and everyday life.

QTM and Central Bank Policy

The quantity theory of money has long guided central bank strategies, especially in the 1970s and 1980s. During this period, many central banks, including the Federal Reserve, adopted money supply targeting to control inflation. Policymakers believed that by managing the growth of the money supply, they could stabilize prices and steer the economy. However, over time, central banks noticed that the relationship between money supply and inflation was not always predictable.

As a result, many institutions shifted focus from strict money supply targets to inflation targeting. Today, most central banks, such as the Federal Reserve, use interest rates as their main policy tool. They set targets for inflation and adjust the policy rate to influence economic activity. While the quantity theory of money still underpins many policy discussions, its application has evolved with changing economic realities.

Inflation, Deflation, and Economic Stability

The quantity theory of money predicts that rapid increases in money supply will lead to higher prices, potentially causing hyperinflation. History provides striking examples, such as Weimar Germany in the 1920s and Zimbabwe in the 2000s, where uncontrolled money printing led to runaway inflation and social upheaval. Conversely, when the money supply contracts or velocity falls sharply, deflation can occur, undermining economic stability.

However, recent decades have challenged the theory’s direct predictions. After the 2008 financial crisis, central banks in the United States and Europe expanded their balance sheets through quantitative easing, greatly increasing the money supply. Despite expectations of inflation, price levels remained subdued for years. These outcomes have reignited debates, especially during periods of stagflation, as discussed in Stagflation and monetary policy. Such episodes highlight the complexity of applying the quantity theory of money in practice.

The Role of Velocity and Financial Innovation

A key variable in the quantity theory of money is velocity, or how quickly money circulates through the economy. In practice, velocity is far from stable. Advances in payment technology, online banking, and digital currencies have reshaped how people and businesses use money. For example, fintech platforms and cryptocurrencies have made transactions faster and more flexible, changing spending and saving behaviors.

Over the past two decades, developed economies have seen a steady decline in velocity. Even as central banks increased the money supply, slower movement of money limited inflationary pressures. This dynamic underscores the importance of monitoring both money supply and velocity when evaluating inflation risks. Financial innovation continues to challenge traditional assumptions of the quantity theory of money and its predictive power.

QTM in the Modern Economy (2025)

In 2025, the quantity theory of money remains a cornerstone of economic analysis, but its role has adapted to new realities. Central banks have experimented with unconventional policies, such as quantitative easing and negative interest rates, to manage economic cycles. These tools have expanded the money supply in ways not anticipated by early theorists.

The recent resurgence of global inflation between 2021 and 2023 has renewed interest in the quantity theory of money. Economists debate whether rising prices confirm the theory’s predictions or reflect unique shocks, such as supply chain disruptions and geopolitical tensions. Policymakers now face questions about whether to return to money supply targeting or continue focusing on expectations and interest rates.

QTM and the Global Economy

The effectiveness of the quantity theory of money varies across countries. In developed markets like the United States, Europe, and Japan, the direct link between money supply and inflation has often been weak, especially when velocity is falling. In contrast, emerging markets with less stable financial systems may experience stronger connections between money growth and price increases.

International factors add another layer of complexity. Global capital flows, exchange rate movements, and differing policy approaches influence how changes in money supply affect price levels. Comparing major economies reveals that the quantity theory of money must be adapted to local contexts, taking into account structural differences and external shocks.

Lessons for Investors, Policymakers, and the Public

For investors and policymakers, understanding the quantity theory of money provides valuable insight into central bank actions and inflation risks. It serves as a historical lens, helping to interpret past and present economic episodes. However, it is crucial to analyze both the money supply and velocity to form a complete picture.

The theory’s simplicity makes it a useful starting point, but not a standalone guide for policy decisions. As financial systems evolve and new technologies emerge, ongoing research and data analysis are needed. Ultimately, the quantity theory of money remains relevant for anyone seeking to navigate the complexities of modern economies.

Frequently Asked Questions about the Quantity Theory of Money

Understanding the quantity theory of money is essential for anyone interested in inflation, monetary policy, and economic cycles. Below, we answer the most common questions with clear examples and up-to-date insights.

What is the quantity theory of money in simple terms?

The quantity theory of money states that the overall level of prices in an economy is directly related to the amount of money in circulation. If the money supply doubles and all else remains equal, the price level is expected to double as well. This theory is summarized by the equation MV = PY.

Does increasing the money supply always cause inflation?

Not always. The quantity theory of money suggests a strong link between money supply and inflation, but this relationship depends on other factors like the velocity of money and economic output. In some cases, governments use tools such as price ceiling effects to limit price increases, which can affect how inflation responds to changes in money supply.

How does the velocity of money affect the QTM?

The velocity of money measures how often money changes hands within the economy. In the quantity theory of money, a higher velocity means that money is used more frequently, which can amplify the impact of the money supply on prices. If velocity falls, even a larger money supply might not result in higher prices.

Why did central banks abandon strict money supply targets?

Central banks moved away from strict money supply targets because the relationship described by the quantity theory of money became less predictable over time. Changes in financial innovation and shifts in the velocity of money made it difficult to control inflation by targeting the money supply alone.

What are the main criticisms of QTM?

Critics argue that the quantity theory of money relies on assumptions such as constant velocity, which rarely hold true in practice. Empirical studies have shown that the direct link between money supply and price levels can break down, especially in complex modern economies.

How does QTM relate to modern monetary policy strategies?

Today, most central banks focus on managing interest rates and inflation expectations rather than directly targeting the money supply. The quantity theory of money remains a reference point, but it is used alongside other tools and theories to guide decision-making.

Are there examples where QTM failed to predict inflation or deflation?

Yes. For instance, Japan experienced long periods of deflation despite rapid growth in its money supply during the 1990s and 2000s. Similarly, after the 2008 financial crisis, major economies expanded their money supply significantly, but inflation remained subdued.

How is QTM relevant for understanding today’s economic environment?

The quantity theory of money helps explain why surges in money supply can raise concerns about future inflation. However, its predictions are most accurate when other factors, like velocity and output, are stable. In today’s world, these variables often shift due to digital payment systems and global financial flows.

Where can I find more data and context about QTM’s historical episodes?

Historical data on episodes like the European Price Revolution, Weimar Germany’s hyperinflation, and recent monetary expansions can be found in monetary history studies. Comparing these episodes provides valuable context for understanding the strengths and limits of the quantity theory of money.

As you’ve seen, understanding the Quantity Theory of Money isn’t just about equations—it’s about uncovering the forces that shape inflation, economic cycles, and policy debates today. If you’re curious to go deeper, explore historical market patterns, or see how money theories play out across different eras, you’re not alone. We’re building a platform to help you connect these dots with interactive tools and expert insights. Want to help shape this experience and bring financial history to life for others? Join our beta and help us bring history to life